In October 2017, four U.S. Special Forces and five Nigerien soldiers were killed in an ambush by jihadists near the border with Mali.

It was a battle that lasted for hours into the night. The highly-trained American special forces were outgunned and outnumbered. They literally had to run for their lives. Were it not for the intervention of French fighter jets from Mali, all of them would have been killed.

The incident jolted American politicians and set off a series of congressional inquiries as to what on earth American forces were doing in an obscure country that most Americans cannot locate on the map.

For the first time, Niger’s mounting security challenges were laid bare.

Up to that point, there were a number of juniors active in the country. They would have known that (a) there was a war next door in Mali; (2) the countryside was unsafe. (In past years, two Canadian diplomats were kidnapped outside the capital, while jihadists seized four French workers in separate incidents.)

Would this incident prompt you to pack up and leave for good?

I’ll be the first to admit this is not easy. People in mining, for the most part, are tough, resilient and eternally optimistic.

And so they slogged it out, hoping the security situation will improve.

Fast forward to 2025. The country’s political and security situation now is a lot worse.

Since at least 2020, foreigners venturing beyond the capital have been required to travel under military or security escort. Both American and French forces were expelled, and a $100 million U.S. drone base in the middle of the country—once key to containing jihadist threats—was shut down.

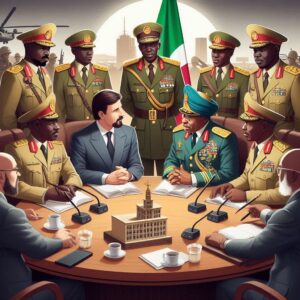

For all practical purposes, Niger is now in the Russian orbit.

Russian mercenaries are all over the country—propping up an (illegitimate) military government.

In return, they want free access to the country’s natural resources. This might explain why the government arbitrarily wrested control of the uranium mines owned by French nuclear company Orano (previously Areva).

Those that stuck around, not surprisingly, have experienced more stress and uncertainty as the security situation further deteriorated. At the time of this writing, one has lost 86% of shareholder value—hundreds of millions of dollars of shareholders’ equity.

Another is at a crucial juncture: mine financing.

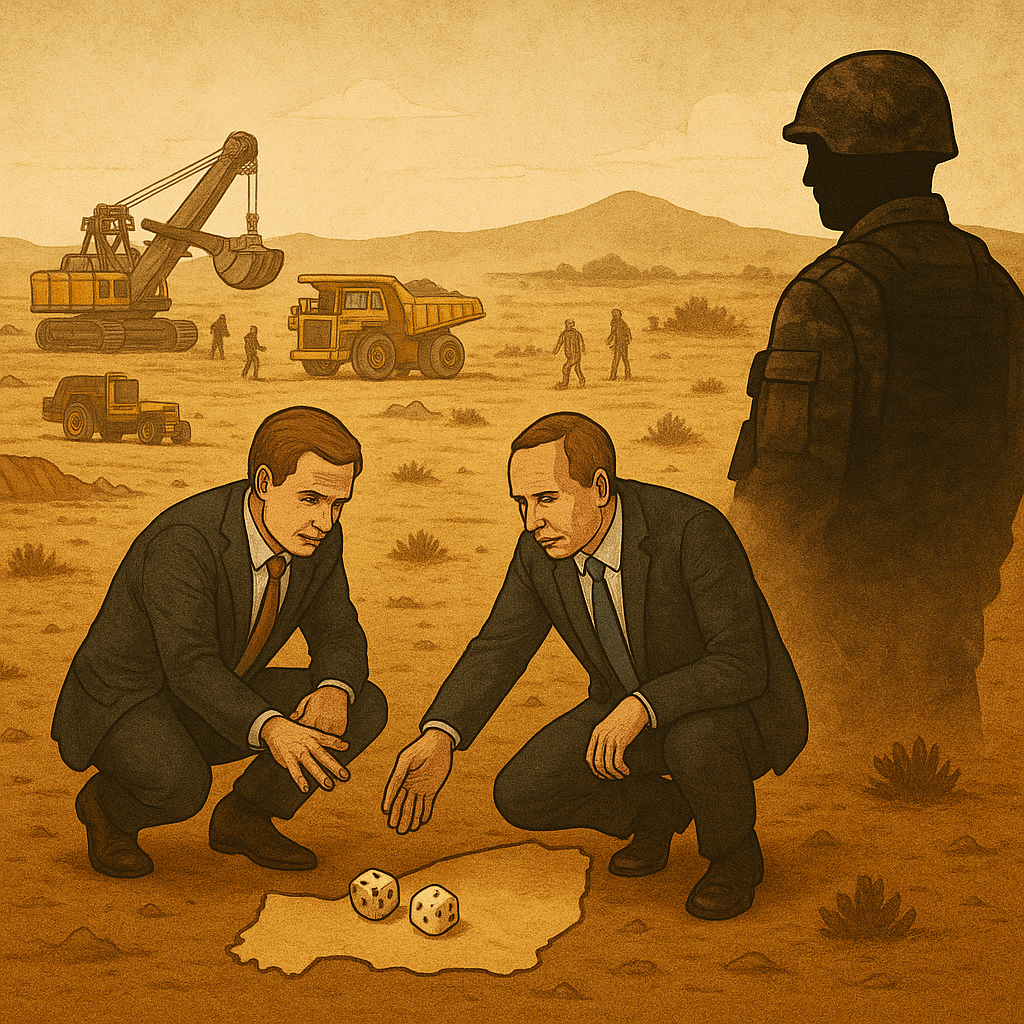

Given the current circumstances, Western investors would be very skittish. If their project is not financeable, then what? Will the government revoke their concession and give it to a Russian company?

In hindsight, management probably wished they’d never set foot there —or that they had acted more like traders. A trader’s instinct is to cut losses fast and get out the moment a crisis erupts.

It’s an instinct that takes time to hone. One thing’s certain: skilled traders don’t throw good money after bad.

(Hai Van Le is the author of Into the Unknown. The novel tells the story of Jake Hall, a 35-year-old geologist working in Mali when he was held hostage by Islamic fundamentalists. The book’s revised and illustrated edition is scheduled for publication in September 2025.)